Set: Tempest (U), Collector #267

Year: 1997

Artist: Thomas M. Baxa

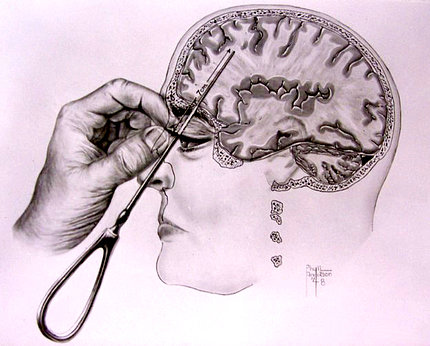

In this week’s edition of “Mind Twist”, we explore the dark subject matter depicted on “Lobotomy”, illustrated by Thomas M. Baxa. Examples of “Psychosurgery” in the form of “trephination” have been found in ancient civilizations across the globe, especially those of the South American continent. Trephination, the practice of boring a hole in the human skull, created a pathway for “confined demons”, which were thought to be responsible for ailments such as headache, seizure and psychiatric illness.

Baxa’s art is reminiscent of instruments used in the Renaissance (1500s), however, “Lobotomy”, as popularized in the 1930s by neurosurgeon Dr. Walter Freeman, often took a “trans-orbital” approach (the “ice pick” method). Psychology 101 students may remember the story of Phineas Gage, an unfortunate construction foreman whose life was forever changed in 1848 when an explosion propelled a tamping iron through his skull. Amazingly, Gage survived and is looked to as an exemplar of behavior reflecting frontal lobe impairment. Post-injury he was seen to have a marked change in his personality to become socially uninhibited, irresponsible, and irreverent. This case study later informed the neurosurgical procedure of selectively destroying parts of the frontal lobe of the brain in order to change the behavior of an untreated or unruly individual – the lobotomy.

Originating from the belief that the frontal lobe could be damaged to alter problematic behaviors, the lobotomy as a phenomenon grew out of necessity as there were more than 450,000 institutionalized mentally-ill patients in a time where effective psychotropics for conditions such as depression, schizophrenia, and personality disorders did not exist. The economic burden of this patient population was roughly equivalent to $24 billion today. Without drug therapy, long-term hospitalization largely consisted of indefinite physical restraint in strait-jackets or padded cells. Other treatments of the era, such as psychotherapy, were out of reach for most patients who either lacked access or the capacity to engage in meaningful talk therapy. It was not until the 1950s that Chlorpromazine, an antipsychotic, was routinely available, a harbinger of the coming psychotropic revolution.

Deinstitutionalization in the 1970s led to a rapid decline in patients in state mental health hospitals, with roughly three-quarters (almost 400,000) of these patients being discharged, many of whom were without the benefit of family or adequate support for their severe mental illnesses. To this day, the legacy of locking away the mentally ill, out of sight to the public, strikes fear into patients who are seeking mental health treatment. In my experience, conversations between doctors and patients suffer due to a well-earned distrust. It is unclear whether disclosing thoughts of suicide, for example, will land a patient “in the looney bin.” Involuntary commitment, although medically and ethically necessary, means abrupt removal from a person’s day-to-day life. Worse, there is no guarantee that a patient will have the resources to function post-discharge.

Tempest, the twelfth magic expansion, takes place on the plane of “Rath.” I will not attempt to describe the storyline, but let it suffice to say that a theme within the set was the use of dark magic to torture those imprisoned at the antagonist’s stronghold. It is clear to me that the man depicted in “lobotomy” is not there willingly. Dare I say, he is involuntarily detained. The implication is that this man is forever changed against his will, likely as a punitive measure or expressly as a form of torture.

The history of psychiatry, and before it the treatment of the neurodivergent, mentally ill, and the criminally insane by court of public opinion, faith healing, or any number of alternative methods, is dark and filled with gross mistreatments of at risk communities. Spotlighting “Lobotomy” provides historical context that led to drastic measures to treat what for most of history was felt to be untreatable. Now, much more refined, ethical, and voluntary practices of stereotactic brain ablation is used in several psychiatric conditions, such as selective “ablation” (laser interstitial thermal therapy) for post-traumatic stress disorder. In lay-man’s terms, we now ask permission before burning small bits of the brain after extensive conversations of risk and benefit, and only after determining whether the patient has the capacity to give permission to have a life-changing surgery. The crude precursors to our modern era rightfully elicited fear of the psychiatric field. Today we strive to learn from the past as imaging and surgical techniques bring about treatments that stand to revolutionize how those who are mental ill are treated and seen by society, and provides hope that debilitating conditions may one day be mitigated if not functionally cured.

Leave a comment